Copyright 2007,

James R. Conner,

all rights reserved.

Updated 31 August 2007. That Governor Schweitzer called a special legislative session to deal with the shortfall in funding for forest fires should surprise no one. Not only did the 2007 Legislature try to fund fighting fires on the cheap, the fire season has been especially severe and a special session might have been necessary even if the Legislature had appropriated more money earlier this year. On that point, David Sirota’s As Montana Faces Fire Emergency, State GOP Embarrasses Itself…Again is worth reading.

What may not be addressed is the need for better, real-time air quality monitoring for fine particulates in western Montana. Smoke particulates are very small, almost always one micron or less, and are, for that reason, very unhealthy (for more information, download the Wildfire Smoke Guide; PDF). Unfortunately, Montana’s air quality monitoring system is not up to the job of providing real-time data on smoke-size particulates during times of smoke pollution. Here’s what I think is missing:

First, the data produced by the eight monitoring stations (Butte, Hamilton, West Yellowstone, Helena, Missoula, Kalispell, Whitefish, and Libby) that the Montana publishes on its website is not presented in real-time. Instead, it’s presented with a lag time of around four hours, what the DEQ calls “near real-time.” That’s not good enough for fire smoke pollution. Instead of relying on objective data, people must assess the quality of the air by relying on eyeball judgments about visibility. Update, 31 August. The delay in reporting particulate levels is down to an hour, sometimes a bit longer.

Second, the DEQ provides only PM10 data for Kalispell, Whitefish, Missoula, and Butte (the other four communities get PM2.5 data). That’s acceptable for monitoring road dust, but not good enough for monitoring fire smoke pollution. At a minimum, Kalispell, Whitefish, Missoula, and Butte should get PM2.5 data.

I would go farther and say that all communities in western Montana with a population of 1,000 or more should be equipped to produce real-time PM2.5 data all of the time.

Why doesn’t western Montana get better air quality data in real-time? Partly, the answer is money. Equipment and the programs to operate it cost money. But I think the larger answer is that a lot of people in industry and government prefer not to know all that much about air quality lest the facts compel them to impose controls on industry, to spend money paving roads, or to risk an uproar by regulating the burning of wood in stoves. Flathead County, for example, has a particulate problem from road dust that isn’t getting cured because the county commission doesn’t want to raise taxes to pave more roads. The commissioners’ recalcitrance plays well politically, but it doesn’t do anything good for our health.

So here are my questions for our Legislature and our Governor: what are you going to do to provide real-time monitoring of PM2.5 and finer particulates in western Montana, and when are you going to do it?

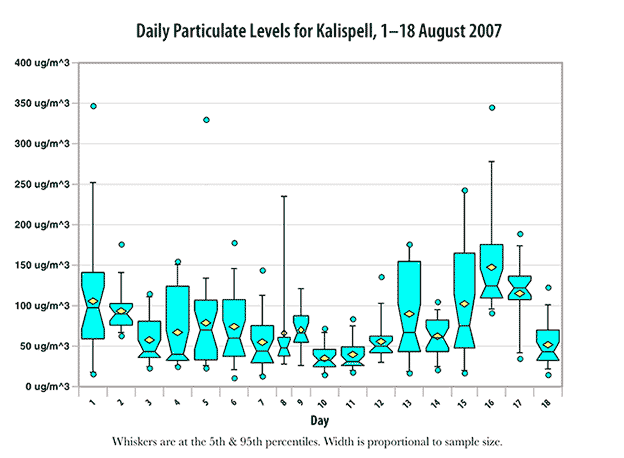

We didn’t need a particulates measuring instrument to know that the air in the Flathead was heavy with particulates for the first three weeks of August. A look out the window told us that. Visibility often was down to three miles or less. And what our eyes told us was confirmed by the air quality instruments atop Flathead Electric in Kalispell.

The hourly readings are available from Montana’s air quality bureau. Below, a box and whiskers plot of the daily averages for the first 18 days of August. What do the numbers mean? Find out here.

That’s the public service philosophy of Flathead County’s 911 Board (you won’t learn much from the 911 website). In a fine story in today’s InterLake, John Stang reports that the 911 board voted to hold a mail ballot election on a tax to fund a consolidated center for Flathead County, but:

Other than that, other details are up in the air, such as: What’s the new center’s price tag? Where is it going to be? What would be its annual operating costs? How much would a tax levy raise each year? What would be the effect on a Flathead County property taxpayer? The Flathead City-County 911 Board hopes to have some of those questions answered at its Sept. 11 meeting.

As far as I’m concerned, the 911 board had better have clear and convincing answers to all of those questions at its 11 September meeting — and a clear and cogent case for holding a mail ballot election in winter instead of putting it on the ballot for the general election in 2008. Far more voters will cast ballots in the general election than in a dead of winter mail ballot election on a single issue.

This behavior does not boost my confidence in the 911 board. I agree that consolidating the 911 centers makes sense. In fact, it should have been done years ago. That’s a no-brainer. And the best site for the consolidated center — Buffalo Hill, near the hospital and Alert base — also is a no-brainer. So why has approving the obvious solution for a long recognized problem produced so much bumbling and dithering? Are the wrong people on the 911 board?

That's certainly a fair question in the case of Diane Smith, who, Stang reports, “…argued that picking a spot prior to the public vote could lead to people fighting over the center’s location,” an opinion not shared by Fred Leistiko, who “…contended that many people would feel more comfortable supporting a 911 center levy with as many details as possible nailed down.”

Leistiko’s got that right. The voters aren’t going to buy a pig in a poke, and it’s irresponsible to ask them to do so. If the voters don’t know where the center will be located, or how the money will be spent; if they sense that the 911 board is conducting a “trust us, we’ll spend your money wisely” election, they’ll vote against the tax in overwhelming numbers. And in those circumstances, that’s what responsible voters should do.

Inciweb is a U.S. Forest Service website that serves as a national source for information on forest fires:

InciWeb is an interagency wildland fire incident information management system. The system was developed with two primary missions: The first was to provide a standardized reporting tool for the Public Affairs community during the course of wildland fire incidents. The second was to provide the public a single source of information related to active wildland fire information.

A number of supporting systems automate the delivery of incident information to remote sources. This ensures that the information on active wildland fire is consistent, and the delivery is timely.

It’s a good idea, but the implementation of it is so incompetent that the honchos responsible for obtaining sufficient resources for it have earned hotel space on the far side of the River Styx. Sometimes I can get to the website, but all too often, and usually in the evening, Inciweb cannot be reached. My browser times out.

Even worse, for several days last week it appeared that Inciweb had disappeared entirely. Entering http://www.inciweb.org in my browser generated an error message of the “this website doesn’t exist” genre. In fact, it was still online and being updated, but I could get to it only by entering the IP number (http://66.60.184.155/) in my browser. That led one expert I know to wonder whether the agency, in order to conserve bandwidth and make the website available to agency personnel, had deliberately made the website invisible to all but those who knew the IP number. An IP number can be found at www.domaintools.com, but few in the general public are likely to know that.

The problem is simple — and so is the technical solution. InciWeb is hosted on a dedicated server by Surewest, an internet service provider in Roseville, CA. Surewest is not that fast to begin with, and a single server isn’t enough for a website that’s intended to satisfy the curiosity of a nation of 300 million during the fire season. The people running InciWeb undoubtedly know this, and undoubtedly have made their superiors aware of the technical solution — but the agency personnel with the clout to provide the resources necessary obviously don’t think that keeping the nation well informed on the fire situation is all that important, and therefore have not fought for resources (dollars) that are needed.

The political solution? Congress must order the agency to increase InciWeb’s bandwith, and must appropriate the money to make it happen. In the meantime, the forests continue burning, and those of us who seek up-to-date information continue to steam.

A huge column of smoke appeared on the Flathead’s southwest horizon late on the afternoon of 31 July as I descended the S-curve on Highway 93 near the county dump. Clearly many miles away, the plume rose straight up, then began streaming across the southern horizon. It was from the Semem Creek Fire (now the

Chippy Creek Fire), burning in heavy timber some 40 miles southwest of Kalispell.

A huge column of smoke appeared on the Flathead’s southwest horizon late on the afternoon of 31 July as I descended the S-curve on Highway 93 near the county dump. Clearly many miles away, the plume rose straight up, then began streaming across the southern horizon. It was from the Semem Creek Fire (now the

Chippy Creek Fire), burning in heavy timber some 40 miles southwest of Kalispell.

Within a day, Montana’s DNRC, the lead agency, changed the name from “Semem Creek” to “Chippy Creek,” justifying the change by reporting that the fire had moved into the Chippy Creek drainage, which it had.

That name change struck me as odd. The conventions for naming forest fires are looser than one might suppose, but usually fires are named for the named geographic feature that is closest to the fire’s point of origin. In the case of this blaze, the point of origin was a lot closer to Semem Creek than to Chippy Creek (see map).

I suspect there was another reason for the name change. “Semem” is just one letter removed from “semen,” and the state’s fire managers recoiled at the thought that a huge column of smoke might be identified as the Semen Creek Fire. So the name was changed to Chippy Creek to protect women, children, and prudes.

Of course, the name “Chippy Creek” is not without its own problems. “Chippy” is street slang for “prostitute.” Chippy Creek is adjacent to Semem Creek. That area must have a colorful history.

I drove across the I-35W bridge frequently when I lived in Minneapolis and attended classes at the University of Minnesota, so the bridge’s collapse is of more than passing interest to me. And some of the reports coming out of Minnesota are more than a little disturbing — and relevant to Montana and other states as well.

According to the Minneapolis Star & Tribune, one of our nation’s better newspapers, the state’s engineers knew as early as 1990 that the structure had problems. By last year, concern was high enough that officials were one step removed from hitting the panic button:

Structural deficiencies in the Interstate 35W bridge that collapsed Wednesday were so serious that the Minnesota Department of Transportation last winter considered bolting steel plates to its supports to prevent cracking in fatigued metal, according to documents and interviews with agency officials.

But instead of strengthening the structure, the state chose to monitor the cracks:

Officials were concerned that drilling thousands of tiny bolt holes would weaken the bridge. Instead, MnDOT launched an inspection that was interrupted this summer by unrelated work on the bridge’s concrete driving surface.

“We chose the inspection route. In May we began inspections,” Dan Dorgan, the state’s top bridge engineer, said. “We thought we had done all we could, but obviously something went terribly wrong.”

Obviously. And what went terribly wrong was the MDOT’s approach to safety. The St. Paul Pioneer Press reported:

More recent inspections in 2005 and 2006 showed no evidence the cracks had grown or that more cracks had formed, Dorgan said. At that time, engineers characterized the bridge as “fit for service,” Dorgan said.

In other words, as long as the cracks didn’t grow, the bridge was safe. Note how logic is stood on its head. When first discovered, the fatigue cracks were considered warnings that something was amiss. But by 2007, the fact that the cracks weren’t getting bigger was considered proof that the bridge was “fit for service.”

The last word on this kind of reasoning belongs to Richard Feynman, the legendary physicist and Nobel laureate who served on the commission that investigated the loss of the space shuttle, Challenger. In his appendix to the commission’s final report, Feynman observed (italics added):

For example. in determining if flight 51-L was safe to fly in the face of ring erosion in flight 51-C, it was noted that the erosion depth was only one-third of the radius. It had been noted in an experiment cutting the ring that cutting it as deep as one radius was necessary before the ring failed. Instead of being very concerned that variations of poorly understood conditions might reasonably create a deeper erosion this time, it was asserted, there was “a safety factor of three.” This is a strange use of the engineer’s term, “safety factor.” If a bridge is built to withstand a certain load without the beams permanently deforming, cracking, or breaking, it may be designed for the materials used to actually stand up under three times the load. This “safety factor” is to allow for uncertain excesses of load, or unknown extra loads, or weaknesses in the material that might have unexpected flaws, etc. If now the expected load comes on to the new bridge and a crack appears in a beam, this is a failure of the design. There was no safety factor at all; even though the bridge did not actually collapse because the crack went only one-third of the way through the beam. The O-rings of the Solid Rocket Boosters were not designed to erode. Erosion was a clue that something was wrong. Erosion was not something from which safety can be inferred.

That the cracks in the I-35W bridge were not growing should not have been construed as proof that the bridge was “fit for service,” which is another phrase for “safe.” It's as though the engineers and politicians had forgotten that the bridge was not designed to crack. The cracks were proof that something was wrong. But instead of repairing the cracks, the Minnesota DOT chose to (a) watch the cracks, and (b) spend $9 million on resurfacing the structure.

Several fires in NW Montana blew up late yesterday afternoon, sending boiling columns of smoke tens of thousands of feet in the air. From my vantage point two miles northwest of Kalispell, I was able to photograph the plumes of the Fool Creek (right; click on an image for a larger version) and Ahorn Fires in the Bob Marshall Wilderness, and the Brush Creek Fire, which is 25–30 miles west of Whitefish. I did not photograph the plume from the Skyland Fire near Marias Pass; it was visible, but not as prominent as the other smoke plumes.

Notes on photography. Isolating the smoke plumes requires a telephoto lens. For the color shots of the Fool and Ahorn (not shown) plumes, I used a 55–200mm zoom on a digital SLR, and, of course, a polarizer. For the infrared image, I used a 200mm prime lens and a Hoya 72 filter (available from www.2filter.com or Adorama). I save the images in the RAW format, and use Photoshop CS3 Extended to bring out the details in the smoke.

The Brush Creek Fire (right; click on the image for a larger version) was to the west, and backlighted. Here I used a 50mm prime lens, exposed for the highlights, saved in RAW, and used Photoshop to equalize the local contrast. I tried making several different exposures to combine into a high dynamic range image, but the smoke was boiling upward so furiously that even a few seconds changed the shape of the smoke column. The beams of light radiating from the sun behind the smoke are crepuscular rays, or in photographer's slang, god beams.

InciWeb has links to Google Earth, which provide an aerial view of the terrain, but not of the fire. This file of Google Earth coordinates will show the location of each fire with map pins.

My back-of-the-envelope calculation estimates that the plume probably reached 26,000 feet. Using photographs taken from northwest of Kalispell, I estimated that the top of the plume reached 3.5 degrees above the horizon. The fire was 65 miles to the southeast. Basic trigonometry (distance in feet times the tangent of 3.5°) puts the ground to plume top value at 21,000 feet, to which the base elevation of approximately 5,000 must be added. This method does not take into account the curvature of the Earth, or apply other corrections.

As of this morning, surprisingly little information is available on the Fool Creek Fire in the Bob Marshall Wilderness. There are stories in the

Daily InterLake,

the

Great Falls Tribune,

and the

Flathead Beacon,

but no information that I could find on the website of the

Northern Rockies Coordination Center.

As of this morning, surprisingly little information is available on the Fool Creek Fire in the Bob Marshall Wilderness. There are stories in the

Daily InterLake,

the

Great Falls Tribune,

and the

Flathead Beacon,

but no information that I could find on the website of the

Northern Rockies Coordination Center.

According to the GFT, the fire is located near Sun River Pass (47° 57' 18" north latitude, 112° 58' 44" west longitude, NAD27), or approximately 64 miles southeast of Kalispell. On the afternoon of 5 July, the smoke plume was visible from much of the Flathead Valley. In the photograph above, taken from a point approximately two miles northwest of Kalispell, the plume is visible above and behind Three Eagles Mountain in the Swan Range.

Update, 1255 MDT. The NRCC’s large incident report now includes the Fool Creek Fire, placing it at 47° 55' 24" north latitude, 112° 59' 17" west longitude; no datum provided (probably NAD83). This is approximately two miles south of Sun River Pass; given the fire encompasses 1,200 acres and is growing, there’s no practical difference between the two positions.

The feds need to do a better job of updating their websites with information on this and other fires. They need to get information up faster, they need to provide precise locations, and all of the forests that manage the Bob Marshall complex need to have fire links on their home pages.

I’ll attempt to calculate the height of the smoke plume this weekend.

The White House is not ruling out a full pardon for Scooter Libby at some point in the future. That’s no surprise — a full pardon always was, and still remains, the mostly likely outcome of this matter.

Commuting Libby’s sentence accomplishes two things. It keeps him out of jail while he appeals his conviction, and it keeps him out of the witness chair in a Congressional hearing.

According to a posting on Talking Points Memo yesterday, a full pardon would prevent Libby from invoking his Fifth Amendment privilege were he haled before a Congressional committee or a grand jury. But once pardoned, his Fifth Amendment privilege vanishes because no legal jeopardy results from testifying to the facts of the crime for which he was convicted and later pardoned.

Since Libby’s appeal probably can be drawn out for the rest of the President’s term, the commutation ensures that the truth about the events that led to Libby’s perjury and conviction will remain hidden from view for the remainder of George W. Bush’s presidency. Then, just before he hands the keys of the White House to the next occupant on 20 January 2009, Bush will grant Libby a full pardon.

Damn clever? You bet. And one hundred percent constitutional.

SB-302, State Senator Greg Barkus’ bill to increase the speed limit on Highway 93 from 65 to 70 mph passed — overwhelmingly — in the legislature’s regular session and was signed by Governor Schweitzer on 28 April 2007. (See Leadfoot Barkus wants faster traffic on Highway 93.) The bill does not contain a section specifying when the high speed limit goes into effect, but I’ve received informal feedback that it will be a bit after Labor Day. In the meantime, the 65 mph limit remains in effect.

Although the increase is just five miles per hour — 7.5 feet per second — it’s not likely to have a positive effect on safety. The kinetic energy of a vehicle increases as the square of the increase in velocity, so the 7.5 percent increase in speed translates into a 16 percent increase in kinetic energy. The implications for a crash are obvious. A second consequence is that drivers have less time to react.

I’m not surprised that SB-302 passed. The ink had hardly dried on the bill that limited Highway 93 to 65 mph before right wing legislators started trying to get rid of the compromise. Approved in 2003, Fortine Republican legislator Rick Maedje’s HB-259 boosted the highway’s speed limit to 70 mph for the winding two-lane road from Whitefish to British Columbia. This was done artfully by redefining the starting point of the 65 mph speed limit:

(2) The speed limit for vehicles traveling on U.S. highway 93 between reference marker 133 northwest of Whitefish and the Idaho border is 65 miles an hour at all times. The speed limit imposed by this subsection ceases to be effective if U.S. highway 93 is upgraded to a continuous four-lane highway.

The increase in the speed limit will not make Highway 93 safer but it will make high-powered drivers with high-powered automobiles who like to drive fast, — a class with a huge subset of legislators — happier. It will not, of course, make these leadfoots as happy as they were when Montana’s daytime speed limit was “reasonable and prudent” instead of a number, but even the most sick of heart over the demise of those wide open days know those times never will come again. So instead of trying to repeal a numerical speed limit, these folks work to legislate the highest possible numerical speed limit.

They do not, of course, argue that their real motivation is “faster is more fun.” Instead, they point out that many narrow, winding two-lane highways have speed limits of 70 mph. “If these roads are safe at 70 mph,” they argue, often with a straight face, “surely a wide modern highway like Highway 93, which is safer than these other roads, would be safe with a 70 mph speed limit.”

If you like driving fast, you’ll find that argument persuasive. But if you believe that the facts should drive public policy, you’ll observe that 70 mph is too damned fast for these narrow, two-lane roads, and conclude not that the speed limit on Highway 93 should be raised, but that the speed limit on the two-lane highways should be lowered to 55 mph.

Barkus’ cosponsors for SB-302 are listed as: Verdell Jackson, Jerry O’Neil, Aubyn Curtiss, John Brueggeman, Janna Taylor (voted "No" on the third reading), Dan Weinberg, Michele Reinhart, Mark Blasdel, Rick Laible, Gary Maclaren, and W. Jones (voted "No" on the third reading). That listed cosponsors voted against the measure is not unheard of. Due to the peculiar rules of the State Senate, signing up as a cosponsor is pretty much a one-way journey.