27 September 2016

Montana seems headed for a lower than average turnout election

Two things happen two weeks from today, on 11 October: (1) election month begins with the mailing of ballots to absentee voters, and (2) regular voter registration closes. Late voter registration, which is deliberately inconvenient, commences the next day, ending at the close of voting on 8 November.

As election month begins, most campaign will switch into their get out the vote mode. Until then, they’ll continue identifying and registering new voters.

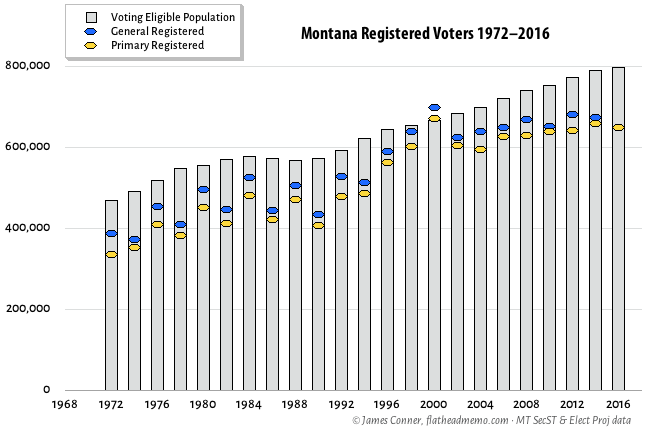

At the end of last week, the Montana Secretary of State’s tally of registered voters (XLS) stood at 666,651, up 17,797 from 648,764 for the 2016 primary in June — but 15,047 below the 681,608 for the 2012 general election.

The voting eligible population for Montana increased from 773,147 in 2012 to 798,787 in 2016. Were the 2012 ratio of registered voters to the VEP to hold for 2016, the tally of registered voters for the 2016 general election would be 704,200. Reaching that number seems highly improbable. In fact, reaching the 2012 number seems unlikely.

In the last two presidential elections, 2008 and 2012, Montana’s registrations increased approximately six percent from the primary to the general. A six percent increase in 2016 would result in approximately 687,700 registered voters for the general election. That, too, seems unlikely.

The number of registered voters does not directly predict how many ballots will be cast. But it’s not unreasonable to suppose that the lack of enthusiasm for registering to vote will be accompanied by a similar lack of enthusiasm to cast ballots. That probably helps Republicans.

The VEP turnout for Montana was 62.9 percent in 2012, 67.1 percent in 2008. At this point, I expect a 57–62 percent VEP turnout for Montana.

In recent years, as displayed in the column chart below, the percent of the VEP that registers to vote has decreased.

None of this is news to the big campaigns. They know how many registered voters are in each precinct, and how many new registered voters are added each day. Those data are available to the public, but only for a $5,000 fee for the statewide file. That’s three orders of magnitude more than Flathead Memo’s annual research budget. I’ll have more later this week on the role and mischiefs of big data in political campaigns.